SHOULD Art be free? SHOULD Artists make money?

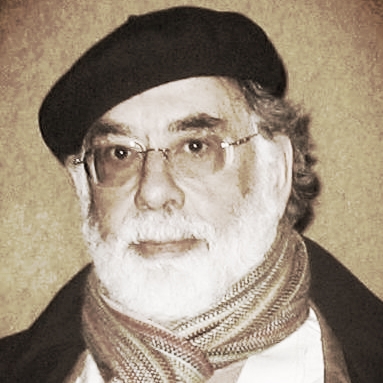

My brother shared a link to an excerpt from an interview with Francis Ford Coppola the other day that immediately caught my attention. The great filmmaker and wine maker (or wine amusement park owner, one might say, but that's another story) recalls a passage from Balzac where he describes weeping tears of joy because a young writer has stolen his prose. Rather than protest that his work has been ripped off, Balzac recognizes that it is part of the youth's learning process to borrow the words of his elders, and that through this sharing process a collective voice is woven that will live on much longer than one individual.

Because that's what we want. We want you to take from us. We want you, at first, to steal from us, because you can't steal. You will take what we give you and you will put it in your own voice and that's how you will find your voice.

And that's how you begin. And then one day someone will steal from you. And Balzac said that in his book: It makes me so happy because it makes me immortal because I know that 200 years from now there will be people doing things that somehow I am part of. So the answer to your question is: Don't worry about whether it's appropriate to borrow or to take or do something like someone you admire because that's only the first step and you have to take the first step...

Bravo, Sir! Welcome to the creative commons! Halelujah! I'm right there with you.

But then Coppola starts to talk about money and art-making, pointing out that:

You have to remember that it's only a few hundred years, if that much, that artists are working with money. Artists never got money. Artists had a patron, either the leader of the state or the duke of Weimar or somewhere, or the church, the pope. Or they had another job. I have another job. I make films. No one tells me what to do. But I make the money in the wine industry. You work another job and get up at five in the morning and write your script.

Red flag.

How many of us struggle to maintain not one career, but two: our (full time plus) career as an artist, and our day job? Bully for you, Mr. Coppola, if you are able to parlay your early commercial success as a filmmaker and resulting celebrity (an important variable, and topic for a future blog post) into a successful wine/entertainment business that financially supports your recent art house films. Well done, sir. But is it not a bit disingenuous to posit, from your lofty seat: "But who said art has to cost money? And therefore, who says artists have to make money?"

The reality is, as you point out, Artists in the west used to rely on a system of patronage, which has disappeared rapidly, particularly in the past 100 years, at an alarmingly exponential rate. (Since the Culture Wars of the 80's we continue to fight tooth-and-nail for any governmental support of the arts--let alone professional artists--in the U.S.) And our economic system does not begin to make up for the loss of patronage with the social systems we need to survive. (So long, health care reform, it was nice meeting you...) So yes, we find creative ways to work for a living, whether teaching, doing admin work at some random business, or maybe utilizing our arts management skills to support another art organization. Then if we're lucky we head to the studio to make our own work. Then we go home and hit the computer, searching for grants, residencies, and sending appeals to producers and festivals all over the country. If we're lucky maybe we get to squeeze in a pilates class so that we stay in adequate physical condition to make this work we're hawking all over the planet.

My question is, Dear Reader: is this sustainable? Is your double-life, your double-career helping or hindering your "real" career as an artist? If you're lucky, it helps. Maybe teaching connects you to your community, trains dancers who you can bring into your company. Maybe you're building networks through arts management or administration. Or maybe filing at a law firm gives you the mental space, the break from your creative projects that you need to be able to focus and be more productive in the studio. Maybe it also gives you the health insurance and vacation time you desperately need.

Or, maybe it's soul crushing, exhausting, and killing your creative energies. What about when your day job swallows up everything else? Is it keeping you from taking the classes that you need to develop as an artist? Is it keeping you in perpetual amateur status? Are you using the safety of your day job to avoid the scary chasm that is the life of the "starving artist"?

And by extension, what message is this sending to the GOP and others who want to cut arts funding because it's "unprofitable" or "useless" and no one really makes a living doing it anyway. We should be very concerned about Art becoming demoted to Hobby in the national imagination.

These are the questions we're wrestling with every day. These are the issues that keep us up every night. So forgive me, Mr. Coppola, if I find your words a bit glib, given your particular situation. "Try to disconnect the idea of cinema with the idea of making a living and money,” you advise us. "Because there are ways around it."

There are creative ways around it, yes. And we are nothing if not resourceful. Artists specialize in making do with what we have, innovating new ideas from limitation, and collaborating with one another. We have talent, vision, and unbelievable energy to make things happen. But I maintain that we also deserve to make a living doing all of this. Where our income comes from, that's an important, long, multivocal debate. I for one just don't think it should come from a day job at Starbucks.

Read the original interview with Mr. Coppola here and tell me what you think.